My friend Leonard lives in metal box in the middle of the Arizona desert. He’s been there for quite some time. Leonard won a scholarship to Princeton University, but wanted more from life than the tenure-track, so he left for the road less traveled. He immersed himself in the jazz music of Greenwich Village and later joined a Zen Buddhist community. Leonard became a drug policy fellow and researcher at Harvard Medical School and Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government and was later appointed as deputy director of the Drug Policy Research Program of the University of California, Los Angeles. That was back in the mid 90s, when his research predicted a fentanyl epidemic in future decades (a warning sadly unheeded by the US Government). Leonard was also a student of Alexander Shulgin and, according to the DEA, the most prolific manufacturer of LSD in history.

Leonard’s metal box measures 2m by 4m, and it contains two beds and one metal shelf. He shares his room with one other person. This is one of the hundreds of similar cells at the United States Penitentiary, Tucson. Though not guilty of any act of violence, Leonard is imprisoned with some of the most dangerous people in the USA. He is serving two concurrent life sentences without parole, having been jailed following a famous bust of a renovated Atlas-E missile silo near Wamego, Kansas, where large quantities of LSD were being produced.

I’ve got to know Leonard via email over the last few years. Our relationship began with Leonard’s book, The Rose of Paracelsus: On Secrets & Sacraments (often referred to as The Rose). This epic work is a semi-autobiographical account, a beautiful and terrifying tale of the clandestine creation and distribution of the psychedelic sacrament LSD. Interwoven with high-level criminal and governmental maneuvering are wonderful poetic descriptions of the psychedelic state. There are deeply moving details of the world that Leonard has conjured from his memory into prose; a world that, according to the terms of his sentence, he may never see again.

The Rose of Paracelsus was my introduction to Leonard and the more I read, the more I was amazed. Here was a wonderful work of literature, written in pencil on looseleaf paper by a man in his remote, cloistered cell. Here was someone who clearly believes in the power of psychedelics to heal, to provide spiritual insight, to make the world a better place. The Rose stands as testament not only to Leonard’s resilience in jail but also as a clear articulation that what this chemist did was, as the Buddhists say, for the benefit of all beings.

Leonard has been imprisoned for 18 years so far. His son and daughter were both born within months of his arrest in 2000. Since being sent to the Arizona desert, he has not seen any living creature other than humans and ants and the occasional pigeon in the dirt exercise yard, nor has he set eyes upon a tree or any other growing plant. There are no roses in that desert.

Leonard is in jail for manufacturing a substance that a growing number of people (from across the political spectrum) recognize, if not as a sacrament, then at least as a legitimate and valuable medicine. If you have used psychedelic substances, it’s quite possible that you’ve used a medicine provided, at incalculable personal cost, by people like Leonard.

But all is not lost for Leonard, or the other prisoners of the ongoing War on Drugs (and people that use drugs).

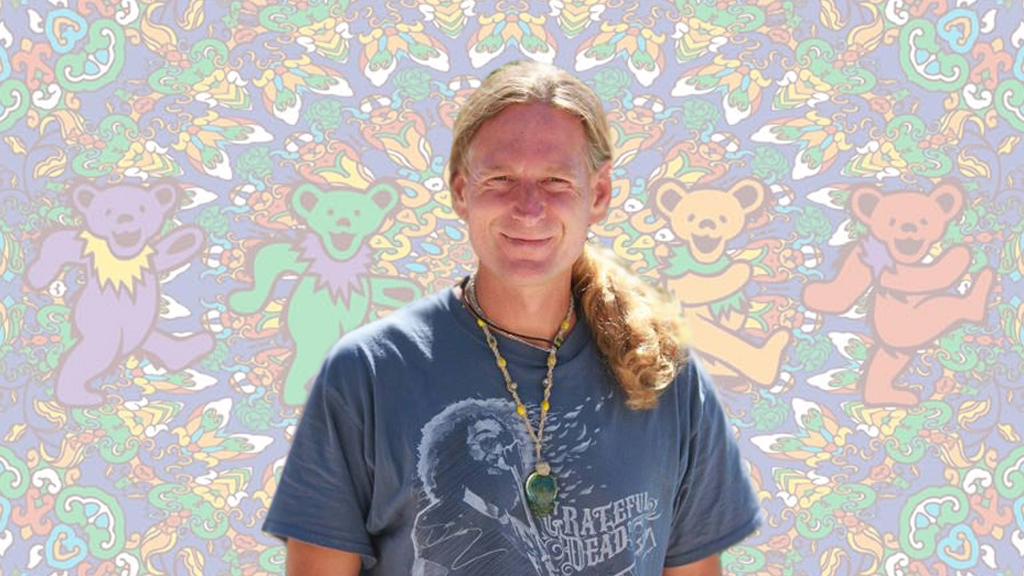

August 2018 saw the release of Timothy Tyler, a fan of the Grateful Dead who had been jailed for life at the age of 24. Tyler, a vulnerable young man, was selling LSD and because of previous drug convictions (for which he was not incarcerated) the judge in his case was compelled, under the federal three-strikes law, to hand down a sentence of life imprisonment back in 1994. This was despite the fact that Tim came from a very challenging background, had never been in any way violent, and was involved in only small scale distribution—selling acid to friends, family and business acquaintances.

Tim’s dad, Timothy Varnum Tyler, was implicated in his son’s drug charges but his son refused to testify against him. Nevertheless Tim’s father received a 10-year sentence and died in prison, just eighteen months before he was due to be released.

Timothy Tyler’s release was the result of a petition that garnered over 400,000 signatures calling on President Obama to grant him clemency. The campaign worked and two years after his petition was accepted, Tim was released.

Tim had it hard in jail. He was denied access to the music he loved. He was forced to take various medications (some of which are now subject to Class Actions in the USA) and repeatedly threatened with solitary confinement. Despite all this, infuriatingly for the authorities, he remained adamant that he considered LSD to be ‘a sacrament’.

Timothy Tyler

Tim is now out of jail. Having entered the dehumanizing machine of the prison system before the millennium he’s now making his way in a world which he says feels “like Star Trek, or Back to the Future!”

Leonard and Tim are two examples of the draconian excesses of the drug war. At one point, they were even in the same prison but were unaware of each other’s presence. While it’s easy to conjure the specter of the evil drug pusher, the reality is that both of these people were providing substances which many people from all over the world have benefited from – and which could land us or them in jail too.

In the United States, 54% of the prison population are incarcerated for drug-related offences. Aside from the despicable fact of disproportionately incarcerating ethnic minority groups, the War on Drugs is also responsible for grotesque examples of unjustifiably harsh sentencing, particularly in respect to psychedelic users.

The annals of the Drug War are full of such examples. United States national Casey William-Hardison was arrested near Brighton, UK in 2003 for producing a variety of psychedelic substances including a small quantity of LSD. He too was not convicted of any violent crime but despite his relatively small operation, was sentenced to 20 years in a British jail. Casey mounted his own defence, claiming that the issue was one of ‘cognitive liberty.’ He was eventually released from jail and deported from the UK after serving 8 years.

The injustices against psychedelic users exist at other levels within the penal system. In the USA there are still many thousands of people in jail for using cannabis. While this is changing in states where cannabis is decriminalized there remain prisoners in US jails serving life for crimes involving cannabis.

While even Fox News trumpets the potential benefits of MDMA therapy and cannabis (‘for our brave veterans’) everyday people across the world are being locked up for possessing and providing those exact same medicines. While many psychedelic users escape prison sentences, other sanctions may be applied to members of the psychedelic community, such as losing one’s job, or being scrutinized by social services as a potentially unfit parent. While the cultural conversation is changing, and psychedelic substances are becoming more accepted, the machinery of the state is slow to adapt and the sanctions keep on coming.

Moreover these injustices are happening even though it’s well known that psychedelic festivals, shamanic ceremonies, and unlicensed therapeutic use of psychedelics are an everyday reality across the globe. In some countries the relatively small number of arrests for psychedelic use reflects the police forces’ lack of interest in these substances. They have better things to do with their limited resources.

We are living in a time that some have called the ‘Psychedelic Renaissance’, a time when there is more licensed research and wider cultural engagement with psychedelics than at any point since the 1960s. This is a time of increasing availability of these substances to licensed clinicians to help people who are suffering, as well as to the general populace. This is also a time in which cultural connections have emerged between indigenous entheogenic communities and the global psychedelic culture. This is a time in which an audience of thousands of people can give a very public standing ovation to former LSD chemist Nick Sand (at the MAPS Psychedelic Science conference, Oakland CA, 2017).

But even in this Psychedelic Renaissance, people like Paul Lee Corbett, a 63-year-old man from Washington State, can still be prosecuted for picking wild psychedelic mushrooms and end up facing a charge punishable by five years in prison. This is also the time in which British medical cannabis activist Jeff Ditchfield can be arrested for possessing a cannabis extract intended for the parent of a child with a severe illness which only that medicine could relieve.

However it’s easy to forget about those incarcerated people living their lives in cramped cells when we’re all so excited about microdosing for better performance at work, or going on ayahuasca retreats, or breaking our depressive cycles with ketamine, or resetting ourselves spiritually with 5-Meo-DMT and kicking our habits with ibogaine… But as a movement and as a global psychedelic community, the plight of the prisoners of prohibition – particularly those in jail for using psychedelic substances – cannot be ignored.

A movement for social change can be judged on how well it treats those who go to prison in defence of its principles; a movement which forgets its prisoners, forgets itself.

We are the lucky ones; we can enjoy the psychedelic films, the Psychedelic Society meetings, psychedelic podcasts and the growing list of resources that are part of our global psychedelic culture. However we should recognize that for the vast majority of us, even for those now operating in licensed or decriminalised settings, our first experiences of psychedelics is likely to have been in a criminal context. Everyday people risk their liberty, and in some cases their very lives, to get these important -some would say sacred – medicines to us. In my opinion we should come together to oppose draconian sentences for psychedelic users, to work to free those still held in jail, and to offer support to the individuals and their families who find themselves on the front line of the War on Drugs.

When I’m high, I remember Leonard Pickard and all those like him, the prisoners of the War on Psychedelic Drugs. I make an offering, in a Buddhist sense, of my ecstasy, my experience, to those medicine carriers and producers who are not free as I am. I like to keep in mind that, contrary to the usual narrative, these are not squalid dealers but people, people like you and me, who took a risk for the things they believe matter. Sure they broke the law, but as Thomas Jefferson said, “If a law is unjust, a man is not only right to disobey it, he is obligated to do so”.

When Timothy Leary was imprisoned in 1970, The Brotherhood of Eternal Love audaciously organised his liberation, but during these days of the psychedelic renaissance we need to go one better. Let’s begin our work to liberate all the psychedelic prisoners, in whatever way we can; acting not out of guilt or pity, but out of gratitude and respect.

To address this issue this site is an element of a new network to support psychedelic prisoners. You can read our mission statement below. If you’d like to get involved please get in touch via our contact form.

Scales

Psychedelic Prisoner Support Network.

“Redressing the balance for psychedelic prisoners.”

- To inform people about the ongoing repression of people who use psychedelic substances, in particular the use of grossly disproportionate sentences and capital punishment against our community.

- To promote psychedelic culture, values, and science, and educating the public about reasons to support prisoners.

- To promote solidarity between psychedelic users, researchers, indigenous entheogenic communities, and other psychedelic advocates and people that are in prison as a result of their relationship with psychedelic substances.

- To support activities intended to help existing psychedelic prisoners, to assist people facing prosecution for their use of psychedelic substances, and to facilitate campaigning by the global psychedelic community on specific cases and broader issues that concern us.

The story of Timothy Tyler is one of hope. Tim is someone from our community who had been sentenced to die in jail but who has been freed as a result of public pressure on government. While there are still many regressive and uninformed opinions about psychedelics in the corridors of power the times, as they say, are a changin’.

Julian Vayne

Very poignant and excellent read, reminds me of Casey’s speech delivered to the World Psychedelic Forum in Basel where he made the point that every trip comes at the expense of a chemist who could lose their liberty. I think he served almost 10 yrs inside not 8.

The greatest thing we can do is to honour the astonishing legal work that he did inside that I assisted with. I understand that now Breaking Convention will do just that by pushing the legal argument that Casey understood but eluded many; WE ARE THE SUBJECT OF THE LAW – ILLEGAL DRUGS DO NOT EXIST!

LikeLike